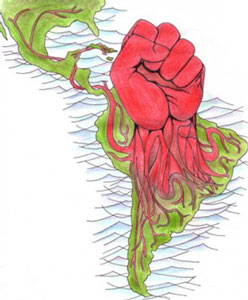

More here from Hugo Blanco....he shows how the revolt in 1962 was a victory for the indigenous...but the fight goes on....mining is the number enemy of the people and the environment.

Ecological politics has to start with defence of ecology and the liberation of people...I would call it class struggle but the vanguard is never the traditional Leninist Party instead like Marx the contemporary left can learn from lucha indigena.

There is a big debate as to the contribution that pre-colonial economic organisation such as the allyu can make to a post-capitalist economy, see Louis Proyect's essay for a way into this.

The ‘Indian Problem’ in Peru: From Mariátegui to Today

(Socialist Voice, March 4, 2007)

I was invited last month by a heroic community to the commemoration of a massacre of campesinos [peasants] who were fighting for land, and who, at the cost of their blood, were able to pass it on to those that work it. The recreation of the massacre was very moving.

I recalled the phrase that was stuck in the mind of Mariátegui: “The problem of the Indian is the problem of land.”

That was the terrible truth. Now it no longer is so.

Before the invasion

Before the European invasion, across the entire continent of Abya Yala (America), individual ownership of land did not exist. The people lived on it collectively.

Unlike in Europe, the development of agriculture and cattle grazing in America did not lead to the emergence of slavery; instead primitive collectivism gave way to other forms of collectivism as privileged layers and privileged people arose. Some forms of slavery may have existed for domestic work, but agricultural production was not based on slavery as it was in Greece or Rome. Rather it was based on collective organization, called by different names in the various cultures (ayllu in Quechua, calpulli in Nahuatl).

Imported latifundio

The European invasion led to the imposition of semi-feudal servitude. The land was stolen from indigenous communities, and the new owners allowed the serfs to use small parcels of land. They had to pay for that concession by working a few days a week on the best land — on the “property” of the latifundista [large landowner], and for his benefit.

This was the central feature of servitude, but more was involved. The indigenous people also had to “pay” with cattle for feeding on the natural grass that “pertained” to the property. The landowner’s cattle was looked after by indigenous people – in return, as “payment,” they received the right to pasture a few head of cattle of their own. The campesinos were arbirarily sent to go by foot through rain and wind for days, to haul loads of products from the “hacienda” to the cities and returning with urban products for the hacienda. Pongueaje and semanería were terms for the forms of domestic service that campesinos had to carry out in the house of the owner.

There were many other obligations, made up according to the imagination of the master. He was the judge, he owned the jails, he arrested whomever he pleased, he physically mistreated someone whenever he felt like it (Bartolomé Paz, a landowner, branded the backside of an indigenous person with a hot iron.) Murders were committed with impunity, and so on.

In Peru, the revolution for independence broke the chains of direct political domination by Europe, but economic dependence was maintained, to the benefit of foreign interests, firstly European and then later Yankee. The latifundio [large estate] system also continued with the implicit suppression of indigenous peoples and the descendents of African slaves.

That oppressive latifundio system, and all the servility it brought with it, began to collapse with the insurgency of the La Convención movement of the 1960s. The indigenous peoples of this country who lived through those times did not struggle in vain; even today, in spite of the many forms of oppression that they still suffer, they can say, “Now we are free!”

End of the hacienda

The high prices obtained for exportable products from the semi-tropical zone of Cusco gave an incentive to the gamonalismo serrano [the ruthless landlord system of the mountain areas] to usurp the land from the communities in the Amazon region. Because the people from the Amazon area refused to be forced into servitude, the landlords moved in campesinos from the mountain areas, who were used to such treatment.

The system of oppression was the same as that in the mountains, but it was exercised in a more forceful manner — in this area the “law,” that provided some slight protection in the mountain areas, did not exist.

The immigrant campesinos suffered due to the climate, illnesses, and unfamiliar food. Large numbers died due to malaria. Work was hard, because they first had to clear the forest before they could start their plantations. Unlike products from the mountain areas, their crops — cocoa, coffee, coca, tea, fruit-bearing trees — could only be harvested once a year.

The greedy landowners demanded ever more workdays per month, while the campesinos, who needed time to cultivate their own products in order to earn any money, sought to reduce the days spent working for the landowners.

In the mountain areas, centuries of exploitation gave the system some protection of custom, but they were challenged on the edge of the jungle areas where this form of exploitation was new. Unions, organized by the Federation of Workers of Cusco, demanded a reduction in the obligations of campesinos to their bosses. They used lawyers to present their claims.

There was some push and shove between landowners and campesinos, some pacts were signed in which the landowners ceded a bit.

But not all the landowners accepted the agreements. The most ferocious would say: “Who came up with this crazy idea that I should discuss with my Indians how they will serve me? I am going to boot out the ringleaders and put them in jail!” And that is what they did, using their close ties with the judicial power, the political power, the police, and the media.

The multiplication of unions strengthened the campesinos. By mobilizing they were able to impede “legal” evictions and get their compañeros [comrades] out of jail. When there was no discussion on the list of demands, the campesinos initiated strikes demanding an agreement. The strikes consisted of not working for the landowners and working on their own parcel of land instead. In that way the campesinos did not suffer as a result of the strikes, as workers or employees do, but rather enjoyed it.

In 1962, after nine months on strike, we unanimously decided in an assembly of unions from Chaupimayo that, since the owner did not want to discuss with us, we would drop our demand for negotiations. On that day, the strike ended and became an “Agrarian Reform.” We decided we would never return to working for the owners, since they had no right to the land — they had not come carrying the land on their shoulders.

The strikes extended across more than 100 haciendas which, though not as explicitly as in Chaupimayo, but rather in an implicit form, produced an agrarian reform in the valleys of La Convención and Lares, carried out by the campesinos themselves.

The landowners went around armed, threatening the campesinos. When the campesinos complained to the police, they responded: “What do you shameless Indians want? You are robbing land from the owner and he has the right to shoot you like dogs!” So the campesinos had to organize themselves into self-defense groups and they selected me to set them up. Afterwards, the government of the landowners ordered repression against us. They persecuted me. They prohibited the assemblies of the federation.

And they began to carry out acts of aggression against campesinos, including the gunning down of an 11-year old child by a landowner. An assembly of four unions ordered me to lead an armed group to bring the landowner to account. Along the way we could not avoid an armed confrontation with the police, where a police officer fell. Later two more fell in another clash. The police massacred unarmed campesinos. After a few months our group was dispersed and its members captured.

Nevertheless, the armed resistance alarmed those in the military that were in the government. They thought: “If these Indians have resisted the commencement of the repression with arms, this zone will burn when we try to oblige them to return to work for the landowners, which they haven’t done for a number of months. It would be preferable to legally recognize what the Indians have done, and thereby pacify the zone”.

And that is how the Law of Agrarian Reform for La Convención and Lares came into being in 1962.

It is true that this helped bring calm

to the area, but it lit up the rest of the country, because the campesinos from other zones said: “Is it because we have not taken up arms that they have not given us land?”

Land occupations were initiated in the mountains, including in the department of Lima. The president of the landowners, Belaúnde, responded with massacres like that of Solterapampa, which I mentioned at the start. Those in the military remained worried that the obsolete semi-feudal haciendas would provoke an expansion of the movement. Given the experience that they had in La Convención, they decided to take power and expand to the whole country what they did in that zone. In 1968, Velasco Alvarado took power and extended the agrarian reform at a national level. The official lack of respect towards the indigenous community appalled the campesinos, but the latifundio, the feudal landed-estate system imported from Europe, was buried.

Now

That is how the axis of the indigenous problem moved away from being a problem of land. Oppression continued, but in other diverse aspects, which were derived from the land problem.

The indigenous struggle continued and continues combating all forms of oppression and achieving advances:

Education: In the era of the latifundio the indigenous population did not have a right to education, despite what the law said. In the midst of the struggle against the latifundio, schools with teachers paid collectively by the campesinos of an area who also constructed the schools, began to appear. (The landowner Romainville kidnapped a teacher and took her as a cook. The landowner Marques ordered the destruction of a school whilst students where still inside; the children fled frightened). After the victory over the latifundio came the struggle that won the right to have schools paid for by the state, and secondary education was implemented. Now there exist professionals who are children of indigenous campesinos.

Healthcare: In this aspect as well, the indigenous campesino sector created sanitary posts with their own resources, and later managed to get the state to maintain them.

The illiterate did not have the right to vote; now they do.

Municipalities: In the era of gamonalismo, it was unimaginable that there could be an indigenous campesino mayor. Now there are a number of municipalities governed by them, some more democratic than others.

There are indigenous people in parliament.

Public order and justice: in many places there has been a partial substitution of the judicial power and corrupt police by organized campesinos.

There is a permanent struggle against corrupt authorities.

Probably the most important struggle today is against contamination from mining.

Neoliberalism attacks campesino products through low prices. There is a resurgence of huge landed estates, no longer in a semi-feudal form, but rather capitalist, with paid workers. The struggle encompasses all aspects of indigenous oppression: social organization, language, medicine, music, customs, native foods, coca, etc.

History, seen with the hindsight of decades, shows us that with the breakdown of the system of semi-feudal servitude denounced by Mariátegui, the floodgates were opened for the indigenous struggle across all fields.

No comments:

Post a Comment